Listen to the episode HERE on Soundcloud or visit the podcast on iTunes, either through the Podcasts App (just search for “Stuff about Things Art History”) or by clicking HERE. Happy listening!

Recommended Sources and Links:

- Shroud.com – Website run by Barrie Schwortz of the Shroud of Turin Research Project. While biased towards pro-authenticity, the website is surprisingly well-balanced, easy to use, and has some great links.

- Books I would recommend for decent reading:

- Freeman, Charles. “The Shroud of Turin and the Image of Edessa: A Misguided Journey.” [skeptic]

- Heller, John. Report on the Shroud of Turin. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983. [leans pro-authenticity]

- Note: In the episode, I mistakenly refer to John Heller as “Robert Heller.” Oops.

- McCrone, Walter on the Shroud [skeptic]

- Meacham, William. The Rape of the Turin Shroud: How Christianity’s Most Precious Relic Was Wrongly Condemned and Violated. Lulu.com, 2005. [leans pro-authenticity]

- Nickell, Joe – various books [skeptic]

- Wilson, Ian – various books [pro-authenticity]

- For a good time, search “Shroud of Turin” on Reddit (glass of wine may be a necessary companion)

- “Shroud of Turin Used to Make 3D Copy of Jesus” [heavily pro-authenticity, but pretty cool]

- UPDATE, 1/16/19: Hugh Farey, a fellow skeptic, generously shared a link to his paper on Academia, which some of you may want to read! See more from Hugh in the comments!

- UPDATE 7/5/19: Joe Marino, a prominent Shroud scholar who believes in the Shroud’s authenticity, has sent me extensive notes via e-mail that he has kindly allowed me to share. Joe worked on the Shroud with Sue Benford, his intellectual partner and wife, before her death in 2009. He continues their work on the Shroud today. In addition to sharing information, he has also suggested corrections and clarifications to some of the information shared in the podcast. Thanks, Joe! Click here to read: email from joe

Related Images:

Gus Content:

Extra Gus Content:

Thanks for listening!

Lindsay

Hi there, Lindsay,

I am a prominent Shroud skeptic, and keep an eye out for fresh mentions on blogs and podcasts, so was delighted to listen to yours. Your whistle-stop tour of the history of the Shroud was entertaining, if somewhat inaccurate in detail, but was I was hoping to hear more about your views, as an art historian, on why you think the Shroud is medieval. Unfortunately really this boiled down to “I can’t believe it’s authentic”, which is hardly a professional point of view. The chief ‘authenticist’ argument is “I can’t explain how it can be medieval!”

Remarkably few art historians have bothered to discuss the Shroud, mostly dismissing it as fake without further explanation, although Thomas de Wesselow spent some time on it, eventually deciding that it must be authentic because “technically, conceptually and stylistically” it didn’t fit any medieval context he could come up with.

I am not an art historian, but I think he was wrong and have explored other contexts in my paper The Medieval Shroud, on academia.edu, which you may care to read. But in the meanwhile, I wonder if I could ask you some art historical questions?

Such as, if the Shroud is medieval, specifically made between 1250 and 1300, is there anything about its design or technique that could suggest where it was made? Does the nakedness, or crossed wrists, or other characteristic point to Germany, England, France or Italy particularly – or maybe to somewhere further east?

Best wishes,

Hugh Farey

LikeLike

Hi, Hugh! Thanks so much for the comment. Your name is very familiar to me from my deep dives into the shroud. I certainly agree with you–my take on the matter isn’t terribly sophisticated or satisfying (dare I say it, not at all). I also wear my bias on my sleeve, which certainly accounts for the inaccuracies and omissions that you rightly point out. When I have time to formulate a thoughtful and informed comment, as you have done here, I will get back to you on some of the questions you pose. Until then, I wanted to let you know that I saw your comment and appreciate it very much, and I look forward to reading your paper on Academia.

All my best,

Lindsay

LikeLike

Hi again!

I was going to leave this for the weekend, but I found some time to read your paper (more on that later in this novella) and brainstorm a response. Due to pressing grant deadlines and a dissertation breathing down my neck, this response is purely off the top of my head based on pre-existing knowledge. I do hope it is partially satisfying or at least stimulating, as it is the best I have to offer you. It is long–certainly more than you asked for or likely expected–so you may want to grab a cup of tea.

As you said in your original comment, I never gave my professional opinion on the Shroud. I sold myself short on that front, as I assumed no one really cared what my professional opinion was. In my episodes, I attempt to replicate the tone and amount of detail I would use to talk to my family and non-art history friends about art history. When I get too technical or off the beaten art history path, I inevitably get told “you lost me.” I also aim to present information in an accessible, not overly technical, and entertaining manner while still striving for accuracy. The Image of Edessa, for example, most certainly did not look like my makeup-smudged face towel–I hope such bits of “information” are taken with entire mouthfuls of salt based on my delivery. I thank you for being exceptionally polite in pointing out that my rapid fire recounting of the Shroud’s history may be inaccurate in certain details. I genuinely mean that–not all Shroud enthusiasts would be so kind in their delivery of constructive criticism. If there are any glaring errors you think should be corrected, I would be happy to clarify these points and provide extra reading materials in the shownotes above.

I smiled as I read the introduction of your paper. I am precisely the audience to which you are referring. I think, however, that there is a more nuanced point to be made about why art historians have avoided the Shroud. Some art historians surely disregard the Shroud full stop, but many of us tend to be an incurably curious bunch, and the Shroud of Turin is the ultimate riddle. Like you, I respect Dr. de Wesselow’s willingness–even bravery–to publish on the Shroud, regardless of whether or not I agree with his findings. Between a lack of primary source documentation pre-1356 and the Shroud’s nearly complete inaccessibility, I unfortunately do not see the Shroud getting art historical treatment any time soon. I hope that I am wrong. Perhaps this perceived “danger” of engaging intellectually with the Shroud for fear of being challenged on so many fronts is what made me pull my punches during the episode. Thank you for calling me out on it–it gives me the opportunity to be more intellectually courageous, though I may already be contradicting that with the forthcoming caveat…

My area of (developing) expertise is Italian art from 1350-1700. Even then, I primarily focus on 1500-1700, but I have dabbled a fair bit. I am not, however, qualified to discuss the possibility of Middle Eastern influences. That will have to remain unsatisfied, at least from me. Additionally, as I state in the episode, I think it is imperative to work not from photographs but from the object itself. Alas, we work with what we have.

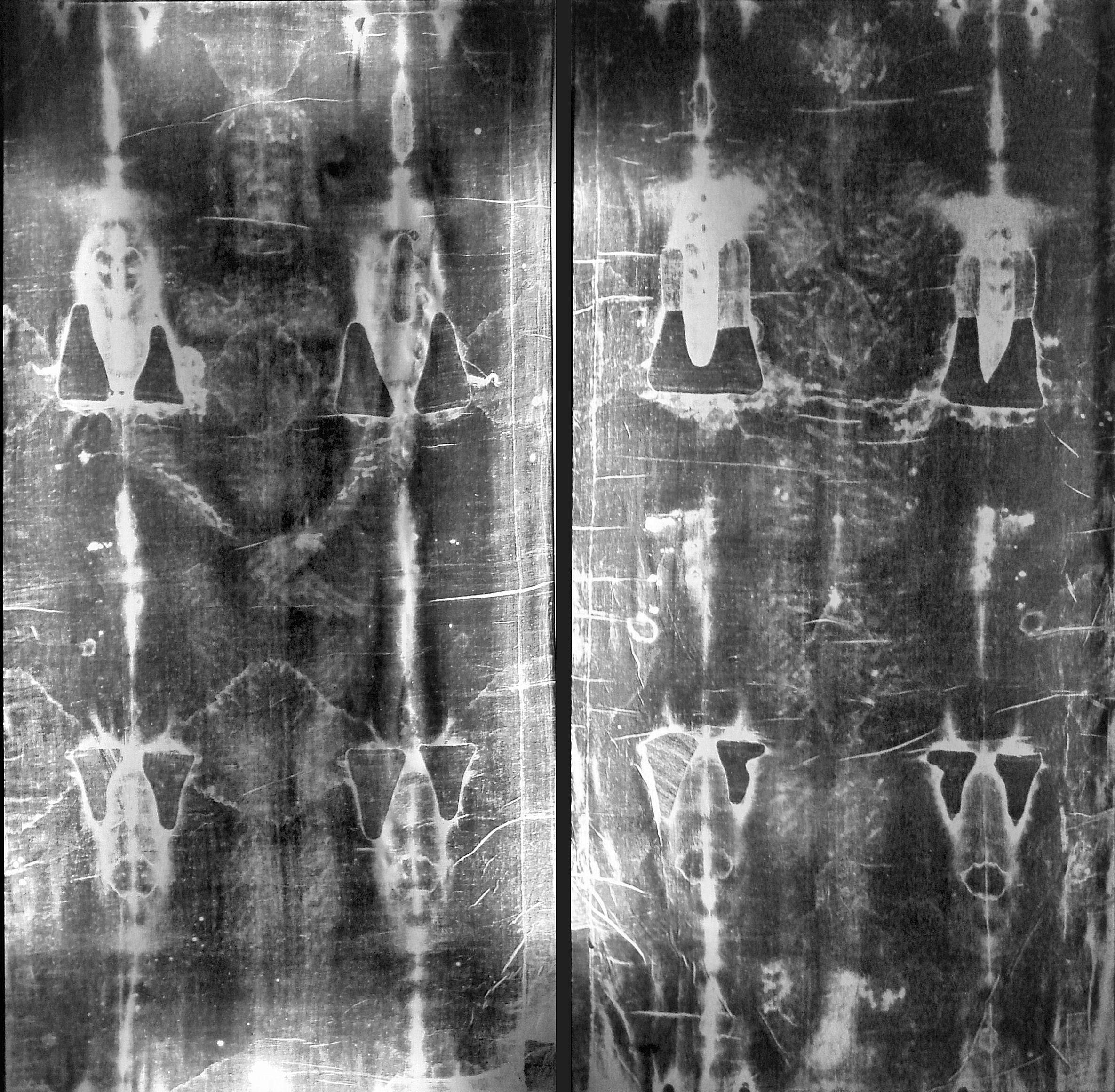

I maintain my casual assertion that “the Shroud just looks fake.” But why do I think it looks fake? And why does it look fake to me as an art historian? First and foremost, I have been trained–both explicitly and implicitly–to identify down to a few decades the period to which an art object dates. Mind you, my margin of error is much greater the further away I get both geographically and chronologically from the Italian Renaissance. As you so rightly point out in your paper, the Shroud also lacks direct comparison. That makes things even harder. If someone were to show me an image of the Shroud of Turin, though, I would estimate that the “image” of the man exhibits characteristics of the medieval period, namely 1150-1350. This opinion primarily comes from my tangential knowledge of bas-relief tomb markers that I encountered while writing a paper about the origins of the transi-tomb in France. I have also seen many such markers in my travels. This assertion will be familiar to you–you mention both gisants and bas-relief sculpture in your paper.

My primary reason for connecting the Shroud to bas-relief tomb monuments is what I perceive to be an inherent flatness to the figure on the Shroud, particularly if we are to believe the image is of a supine man. While some sindonologists and scientists have asserted that the Shroud is a “three-dimensional image” (my vocabulary is off here, but I am confident you will know to what I am referring), my visual instinct is to disagree. It is only with computer enhancement that the three-dimensional nature of the image comes into relief (forgive me for the pun). I strongly question the validity of that methodology, even if I think it is thought provoking. Granted, my approach of “It looks flat” is not methodologically sound at all. I fear both sides of this argument suffer from acute confirmation bias. I see a bas-relief in my head, so I naturally associate it with a bas-relief. Others think it is a human impression, so their own brains make sense of the image as thus. I think that is the brilliance of the Shroud, whether deliberate, happenstance, or divine: it is ambiguous enough that the viewer sees what he or she wants. It is what makes the topic so maddening.

If pushed, I would specifically say it is particularly reminiscent of those from Northern Europe rather than somewhere like Italy or Spain. In your paper you mention the Sienese school of painting, which is interesting and I can see the merit in that. I think it would be more likely, however, to consider the mixing of Italian and French styles at the papal court in Avignon rather than the Sienese school specifically. Either way, the proportions of the figure on the Shroud look elongated to me. My eyes are especially drawn to the hands. The fingers seem far too elongated and simplified to be considered anywhere near “anatomically flawless,” especially those of the figure’s left hand. Next, my eyes are drawn to areas that are missing–the groin is sketchy, the feet nearly illegible. The former suggests modesty, which may also account for the elongated fingers of the left hand; the latter potentially points to the selective exclusion of an area that might be difficult to render. I am not terribly familiar with the effects of rigor mortis on feet (thank goodness) other than what I remember from a trip to an anatomy lab, but I presume that they would point upwards or outwards at some kind of angle, which I imagine would be very tricky to render. Visually speaking, the only “sign” of the feet I can make out is the stigmata marking. Given that that mark is so vivid, you would think the feet would be, too. A devil’s advocate would certainly poke holes in this logic as well as point out that that area of the cloth appears to have water damage, which may have reduced the clarity (“clarity” being a relative word where the Shroud is concerned) of the image. The blood marks all over the body also look unnaturally deliberate compared to what I would expect of extensive flagellation, even one featuring a whip that would produce several marks on one blow. My limited knowledge of German art makes me think of print depictions of German “wild men,” who are depicted with a pattern-like “coat” of hair. I do not know how one would illustrate what natural flagellation marks would look like without volunteering for demonstration–to which I say “no thanks!”

As for the depiction of “Jesus” in the Shroud image, it seems prudent to start with representations of Jesus’s dead body in and around France. As a Renaissance/Baroque scholar, my way forward would be similar to a car stuck in mud: I’d start with what I know (drive forward, hoping to get some traction) before finding my way back to the middle ages (gunning it backward). I would personally start looking at transi tombs as well as those of French sculptural groups of the lamentation. I would consult William Forsyth’s work on French sculpture first and let his footnotes lead me forward. I have only read his 1970 volume on entombments–read it years ago–but I believe there are others. His work tends to concentrate on late medieval / early Renaissance but I am confident he mentions earlier traditions, at least in the Entombment one. There’s also a relatively new 2012 volume edited by Donna Sadler regarding such sculptures. I have a hunch–again, I cannot really explain it–that studying sculptural representations of Christ may be a more conducive avenue to elucidating why the Shroud figure might look as he does. Despite my earlier assertion about the inherent “flatness” of the Shroud figure, I tend to think in sculptural terms, given that most of my work is on sculpture. I personally think that a forger would be better off looking at a sculpture if not a real body than a painting for inspiration, though I think you disagree with that in your paper.

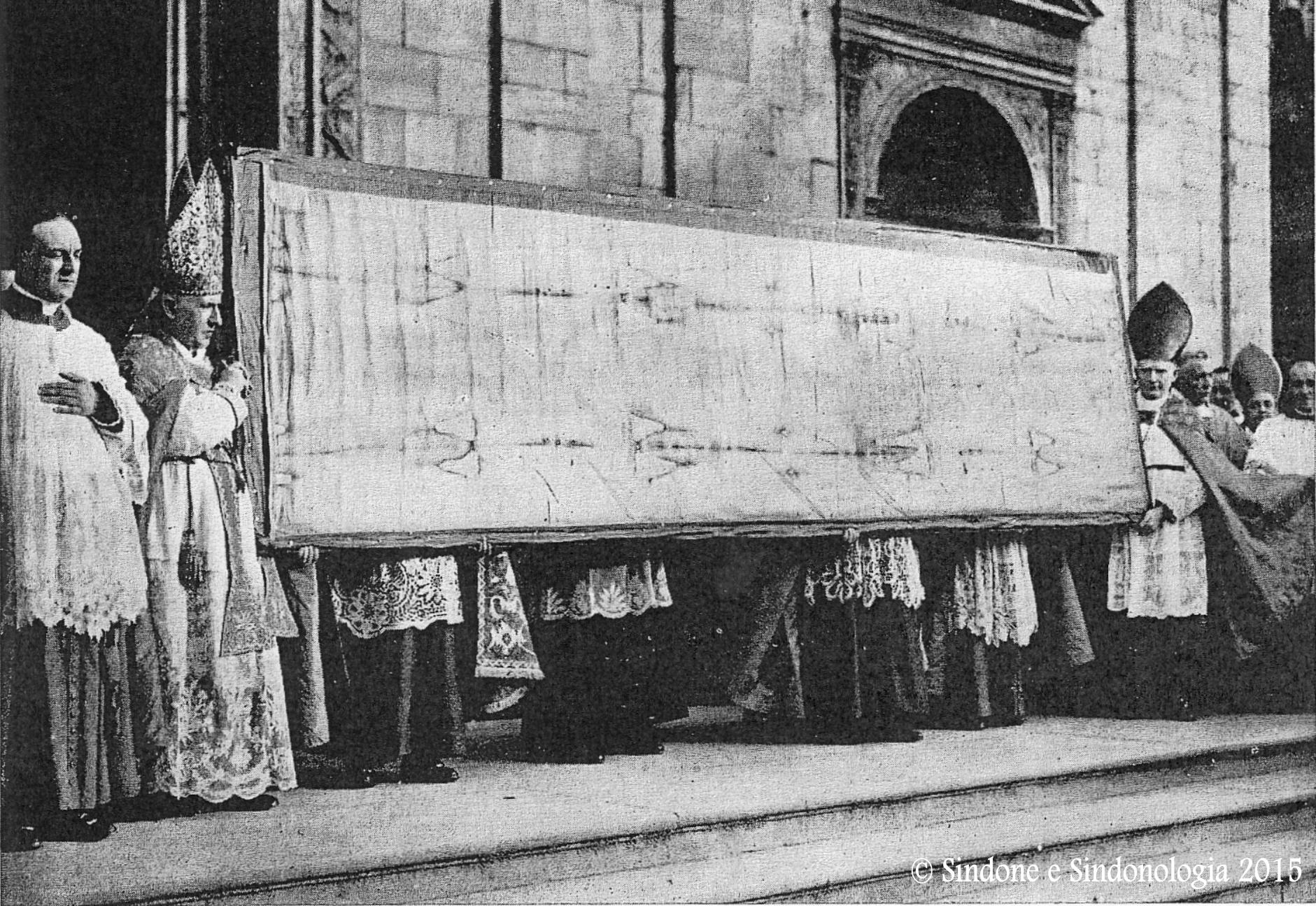

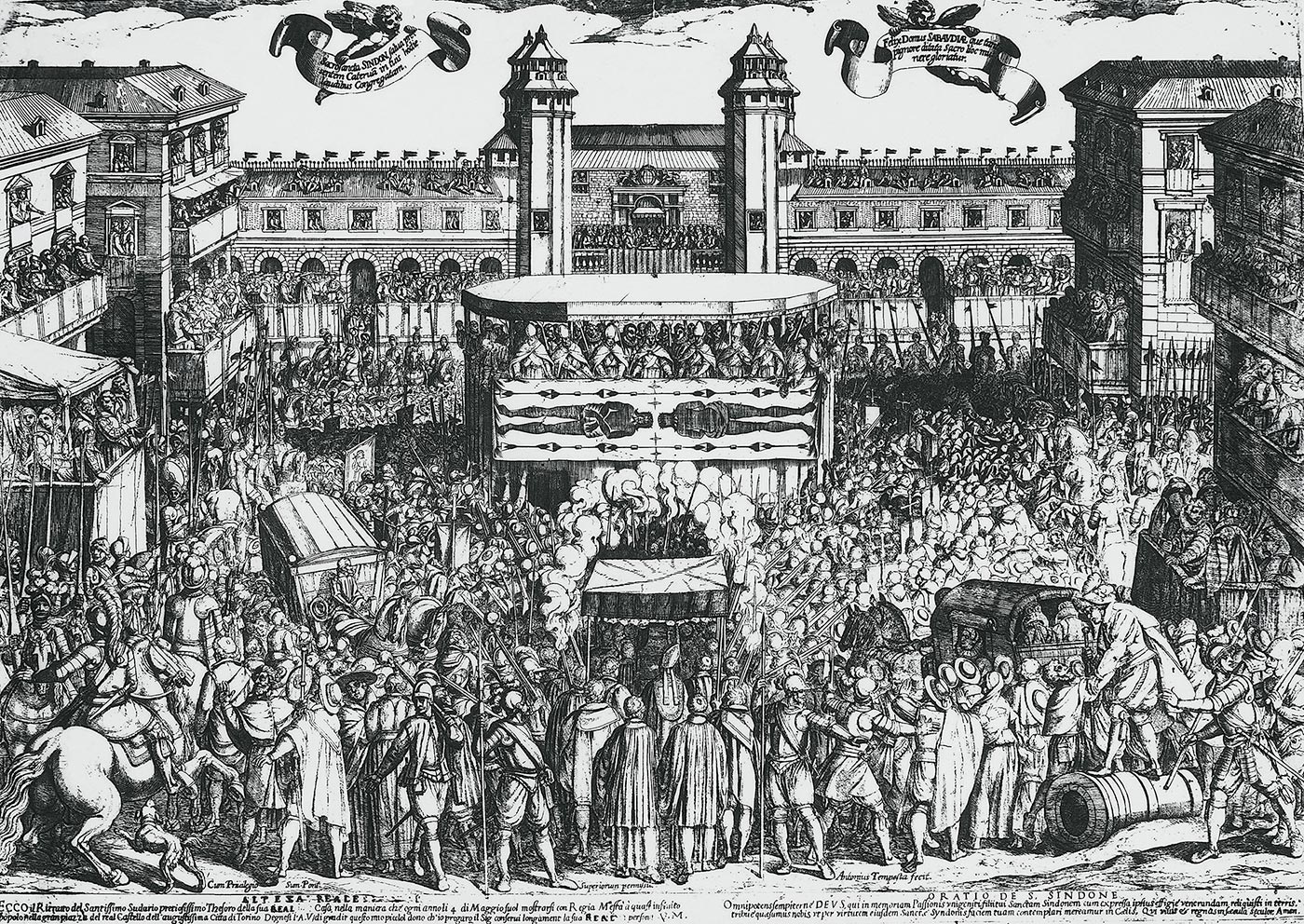

I would start with representations of the dead Christ because I think that would be more fruitful than belly flopping into questions about how the Shroud was made. Well, how was the Shroud made? I, like everyone else, have no idea. You provide an excellent summary of proposed methods in your paper. Lost technologies, indeed. If I were to look into it, I would follow in the steps of Freeman and McCrone in researching methods of art making but also of art conservation, of textile craft, of early printing, of any examples of super duper early versions of photography anywhere in the world. I also believe that there is a false dichotomy between “authentic” and “forgery.” As you point out in the paper, prop shrouds were common. Objects were often used in the middle ages to stimulate worship in a variety of environments. I try to entertain the idea that the intention was not always to dupe, though relic forgery was certainly a lucrative business. If the Shroud was indeed made not as a forgery but as a simulacra of the Shroud intended to facilitate worship, that function was shed in the late 1300s, as you point out in your discussion of Lirey, the arma Christi, etc.

I have only encountered the Shroud a few times in my own research, and even then I only ever encounter it through mentions of replicas. You mention these briefly in your paper. If I were to look into the creation of the Shroud, I personally would start with the replicas. My original dissertation topic was the Sacri Monti of Northern Italy. While my topic changed, I am fairly well read on my original topic, the research for which brought me in contact with an article by Casimiro Debiaggi entitled “Su una scomparsa riproduzione cinquecentesca della Sindone già al Sacro Monte di Varallo” (“On a lost sixteenth-century reproduction of the Shroud once at the Sacro Monte of Varallo”). I had to request the article via Interlibrary Loan. Without re-reading the article, I believe there was a full size reproduction of the Shroud at the Sacro Monte of Varallo. It’s now lost, but I believe the article does go into a bit of history regarding Shroud replicas. How were those made? How true-to-life were they? These are some questions I would start asking and see what I could find and how far back history could take me. It might be a dead end, but at least it would be a good start?

What this all comes down to is that when I look at the Shroud, I see a carefully curated image. I see a flattened quality, elongated proportions, too-uniform wounds, blood stains that are too neat, areas that seem strategically omitted… the list goes on. But I am also looking for reasons to say it is “fake.” I have tried switching to a different perspective, but I cannot shake the skepticism. I am, it seems, a very flawed member of the jury of the Shroud of Turin.

Now that I have said all of that, please also allow me to say that I enjoyed your paper immensely. I regret that I did not read it before recording the episode. I have since linked it in the sources above so that any visitors will have it at their disposal. I decided to insert this note here rather than above so no one can accuse me of brown nosing before attempting to answer the questions you had posed. ☺

I fully expect that even this explanation is full of holes, maybe even a few (or more!) landmines. I also regret any grammatical mistakes. I only had time for a quick spell check in Word. Alas, this is the best I can give. If nothing else, I hope it gives you at least one new idea of where your extensive Shroud studies might take you next!

Wishing you good luck and good skill,

-L

LikeLike

What a splendid reply. I think I write best when I’m meant to be doing something else much more important too! But thank you for your agreement that Avignon seems at least one good focus for art historical interest. Simone Martini, if we had to choose a named artist, would fit the bill quite well, but I don’t know any studies exploring the effect on Italian art of the papal move to France. I have read both Forsyth and Sadler, and they are both tantalisingly close to the subject, but would seem to place it further north, in the sepulchre sculptures of Germany (The ‘Holy Graves’), from which their particular subjects seem to have been derived. On with the exploration!

LikeLiked by 1 person